Tucked away in a little known corner of southwest Madagascar lies the remote fishing village of Andavadoaka, where life is intertwined with the turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean and the motto of the people is “Velo-andriake” – to live with the sea. The Vezo have lived by that motto for generations, feeding their families and basing their livelihoods on a unique relationship with the ocean, assisted by their hand crafted sailing boats called pirogues or ‘Laka’ in which the fishers glide effortlessly across the sea.

Photo: Garth Cripps

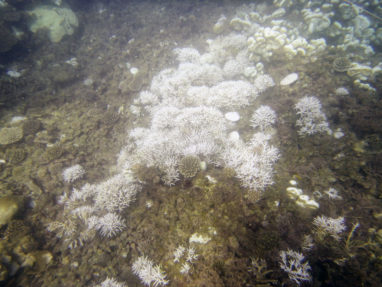

But the reefs that support the livelihoods of the Vezo families here are facing a challenge. The austral summer season of 2015/16 has been hotter than normal, causing a mass coral bleaching event that has severely affected the reefs around the world, putting them at risk of collapse. In southwest Madagascar this event brings the livelihoods of the Vezo families into jeopardy, as the reefs support a high abundance of marine life.

Blue Ventures, with the help of their marine conservation volunteers, are currently monitoring the reefs, the bleaching event and the hopeful recovery of these reefs on a local scale. Travelling to Madagascar from across the world, volunteers stay and work in the village of Andavadoaka, train in coral and fish species identification and underwater surveying before assisting the Blue Ventures field scientists with data collection, including the crucial coral bleaching surveys.

The work of the volunteers provides vital data on the health of the reef and the changes that are occurring over time, including the occurrence and longevity of bleaching. This data is then uploaded to a bleaching database for the Western Indian Ocean, which is contributed to by hundreds of other scientists and organisations, and which provides bleaching alerts for the region, as well as high quality up to date information on current bleaching levels and recovery.

In this way the work carried out here in Andavadoaka by volunteers and field scientists contributes hugely to regional efforts to monitor the bleaching events so that we can learn how best to mitigate their effects in the future. It has been a huge honour to be a part of this process over the last six weeks.

From the first time I dived below the water’s surface in Madagascar it was evident that the corals were in a sorry state.

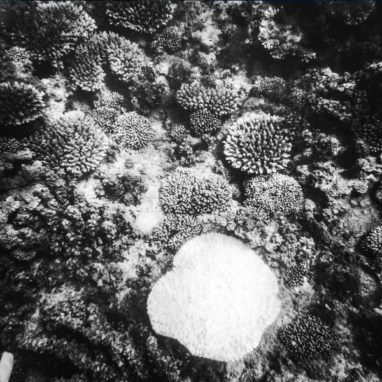

Even an orientation dive revealed huge metre-wide colonies of luminously white corals, sending instant shivers down my spine. This was first-hand evidence of our changing planet confronting me face-to-face. Despite years of studying Earth Science at university and understanding many of the grave implications of climate change, both present and future, this was a tangible consequence displayed right before my eyes. I felt shocked, saddened and humbled by the global scale of the impacts of climate change, but most surprisingly I felt motivated. This was what I came here to do. To contribute to the protection of our oceans in some small way. The reefs need us, they need Blue Ventures and other organisations like them, a union of scientists around the world assessing how coral reefs respond to all of the anthropogenic and environmental threats and stresses that are thrown at them. They need governments and international policy makers to listen to these reports and take action, and finally they need me, and the tiny part I am playing in this global mission.

For the most part, I am firmly engrossed in coral, studying hard, and diving every day to record the benthic fauna, but in the quieter moments I am haunted by my fear for the local communities should the coral fail to recover. The sea is the village’s lifeline – on good days fishers go out in the early hours of the morning, returning with octopus, squid, grouper, jacks and even tuna, selling the produce to other villages or feeding their own families. But on bad days, fishers return with nothing, or are prevented from fishing by the weather, leaving their families struggling for money and with no fish to eat.

If the reefs don’t recover then the productivity of the fisheries will decrease, and there will be more bad days where the fishers don’t bring home any catch – a prospect that doesn’t bear thinking about.

Photo: Amelia Johnson

With luck, this future will not come to pass. The reef is already starting to show some positive signs of recovery. However, we need more than just luck. We need communities like those in Andavadoaka to come together to manage their marine resources, making them stronger and more able to resist and recover from stresses. We need organisations and volunteers to help with this process, and we need people across the world to mobilise themselves, pressuring their governments and international bodies to take real and significant action to limit global climate change so that coastal communities can continue to live with the sea for generations to come.